Age of weather extremes

The participants in the World Climate Conference in Glasgow, which begins at the end of October, have a huge responsibility. Floods, storms, heat, droughts, fires: The climate crisis is becoming more apparent than ever before. How Germany must adapt to this - and what role insurers play in the process.

Consequences of the flood: The city centre of Euskirchen and the Erftstadt district of Blessem submerged in floodwater

On 27 June 2021, a murmur went through the world of meteorology. On this day, the thermometer in Lytton, Canada, rose to 46.6 degrees Celsius - higher than ever before in Canada. On 28 June, the first foreign media reported on the community not far from the winter sports paradise of Whistler; the local weather station now reported 47.9 degrees. As the thermometer stood at 49.6 degrees on 29 June, news portals around the world brought news from Lytton. How high the temperature rose on 30 June could no longer be determined beyond doubt. On that day, a firestorm destroyed the small community. It is not unusual for heat records to be set. It happens all the time, just as parched forests and scrubland are always going up in flames somewhere in the world. Nevertheless, the Lytton disaster is exemplary. It marked a new phase in the global climate crisis. Never before have its catastrophic effects been so tangible as in this summer of extremes in the northern hemisphere.

End of May: 31 degrees at the Barents Sea in the Russian Arctic. Early July: 33.6 degrees in the north of Finland. Mid-August: 47.2 degrees in Andalusia and 48.8 degrees in Sicily. Many highs of this summer are no longer measurable with fever thermometers, their scale reaches only to 42. When decades-old records have been beaten in the past, it was by a tenth of a degree or two. Now they are being pulverised. At the same time, the forest fires around the Mediterranean, in Siberia, in Canada and on the east coast of the United States are reaching a scale that is beyond anything previously known. But heat and fires are only one thing. At the same time, hurricanes chase across the Atlantic, western Germany sinks in flood waters, rainfall in China triggers flash floods and landslides in Japan. At the highest point of Greenland's ice sheet, 3200 meters above sea level, rain rather than snow is falling for the first time since records began. The entire article could be filled with a list of examples of extreme weather swings, from this year alone.

It is getting hotter and drier. At the same time, there is more heavy rain and flooding

The authors of the latest world climate report have described what all this means both soberly and unsparingly: Man is changing the face of the earth ever faster and on an ever greater scale. The greenhouse gas emissions this causes, above all CO2 and methane, have already increased the global average temperature of the earth's atmosphere by a good 1.1 degrees compared to pre-industrial times. The consequences are dramatic. Sea level rise is accelerating, as is the mass extinction of animal and plant species, which has not occurred in this form since the disappearance of the dinosaurs. The risks of droughts, extreme heat waves and forest fires are increasing. At the same time, it is getting wetter in many places because the heated atmosphere is absorbing more moisture. Storms and heavy rains tend to last longer and become more severe, making floods and flash floods more likely. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), if the temperature increase is to be limited to 1.5 degrees, humanity may have ten years left to act. The participants in the climate conference in Glasgow, which begins at the end of October, therefore have a huge responsibility. The heads of state and government cannot afford to fail.

"This shows the force with which the consequences of climate change can hit us all and how important it is to be even better prepared for them."

Reality is following the forecasts of climate researchers. Faster than expected

You can't say the world wasn't warned. Climate researchers have been predicting this development for decades. As early as 1856, the American Eunice Newton Foote experimentally proved the greenhouse effect. in 1896, Svante Arrhenius described how humans are warming the climate by burning coal. in 1958, American Charles D. Keeling began a long-term measurement of atmospheric CO2 levels that is still ongoing today. The data set became famous as the "Keeling Curve", running from bottom left to top right. Some of the most accurate forecasts come from, of all people, those responsible for the climate crisis: Researchers from the oil company Exxon described the expected course of the temperature rise with amazing accuracy as early as 1982. Their study immediately disappeared into the drawer. Finally, in 1995, Klaus Hasselmann, a German recently awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, succeeded in demonstrating the much-cited "fingerprint of CO2" in climate change. What surprises scientists today are not the consequences of global warming that can currently be observed everywhere. It is the speed with which they are occurring. For a long time, researchers expressed conservative views. To avoid being considered alarmist, they tended to describe the milder end of the range of their expectations. When they were asked whether individual weather events could be attributed to climate change, their standard answer was that this could not be answered seriously.

Storm damage in Germany (1/2)

2002 - Flood on the Danube and Elbe: The first "flood of the century" of the new century.

2005 - Snow chaos in Münsterland: Power poles buckle under the ice load.

2006 - Elbe flood: Another "flood of the century", just four years after the last one.

2007 - Hurricane Kyrill: Wind speeds of up to 225 km/h cause damage worth billions.

2010 - Snow chaos: Hurricane Xynthia and Storm Daisy ravage northern Germany.

2013 - Hail in Reutlingen: Ice projectiles the size of tennis balls pierce roofs and cars.

But the time for restraint is over. In the meantime, a new scientific discipline exists, so-called “attribution research”. One of its founders is Friederike Otto, professor at Oxford University. The Kiel native, co-author of the World Climate Report, studies extreme weather events while they are still ongoing. "We compare the weather we observe in the real world to that of a fictional world where man-made greenhouse gas emissions do not exist", Otto says. She and her team are feeding supercomputers real-time data to calculate whether and to what extent global warming is partly responsible when storms rage or rivers become inland seas in a steady rain. They do not always arrive at unambiguous results; hailstorms, for example, occur on such a small scale that they are extremely difficult to calculate. But in many cases, researchers are confident of clear answers. The heat wave, for example, that caused Lytton to burst into flames was "virtually impossible" without the greenhouse effect, she said. Attribution researchers also analysed the July floods on the Ahr, Erft, and Maas Rivers in Germany and Belgium. Result: Even the current rise in temperature has increased the risk of such a catastrophe by up to nine times, she said. "The results show that it is becoming increasingly important to take into account such extreme and very rare events", researcher Maarten van Aalst, who was involved in the study, told Deutschlandfunk Radio. "Because climate change will make them more likely in the future".

"Adaptation to the impacts of climate change must drive all of our actions, day in and day out, and become mainstream."

Cities need to become resilient: Resistant to heat and flood

The researchers' warnings seem to have reached at least some politicians. "Climate change has arrived in Germany", tweeted German Environment Minister Svenja Schulze after the flood. “The events show the force with which the consequences of climate change can hit us all and how important it is to be even better prepared for such extreme weather events in the future". In practice, however, federal, state and local governments often struggle to come up with the right response. There was no lack of good words and noble goals, explained Jörg Asmussen, Chief Executive Officer of GDV. "However, there is a huge gap in implementation. Adaptation to the consequences of climate change must determine all our actions day by day, and become mainstream". Researchers have long since described the necessary tools for this adaptation. You talk about Germany having to become "resilient". In psychology, this term describes the ability to cope with strokes of fate. In terms of the climate crisis, it means withstanding extreme weather events.

Storm damage in Germany (2/2)

2016 - Flooding in Simbach: After heavy rain, a brown avalanche shoots through the place.

2017 - Floods in Berlin: Once again, there is talk of an "event of the century".

2018 - Heat wave: Low water in rivers such as the Rhine and Elbe stops shipping.

2019 - Heat wave: Fields dry up, Emsland reports a temperature record of 42.6 degrees.

2020 - Hurricane Sabine: Blocked tracks, collapsed roofs and at least 14 dead across Europe.

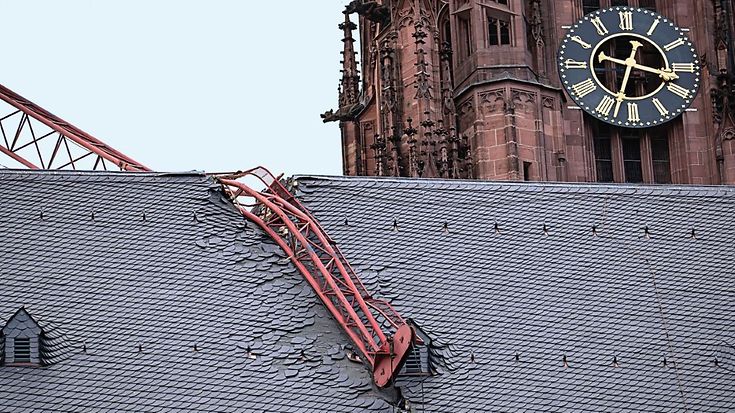

2021 - Flood: Repairing the damage caused by the Bernd rainstorm will take months.

In Germany, the greatest climate risk comes from temperature. The number of hot days of more than 30 degrees is increasing. Until the nineties, ten hot days per year were extremely rare. In 2018, there were already 20. In the southwest of the country, temperatures of well over 40 degrees are even possible in the future, as was recently the case on the Mediterranean. When it is this hot for days or weeks at a time, it becomes life-threatening for the elderly, the sick, and young children. This is illustrated by the well-studied heat wave of 2003, which claimed the lives of 70,000 people across Europe. Cities are heating up particularly strongly. Asphalted surfaces, stone buildings and office towers with glass facades turn them into glowing ovens. The best antidote is green spaces: Trees and overgrown facades act like urban air conditioners; in their surroundings, temperatures are several degrees lower. Green roofs, parks and swales also help combat the second major climate threat: water. During heavy rains, plants absorb some of the floodwaters, relieving the strain on the sewer system. Urban planners speak of the concept of a "sponge city" that soaks up water when it rains and later releases the water in measured doses. But free space is a scarce commodity in cities. Where parks are created, houses cannot be built; in many places, residents are fighting over every parking space that is to make way for a tree. Even outside the urban centers, more and more land is being sealed. In the event of heavy rain, water is thus diverted into rivers, streams or the sewage system, causing water levels to rise.

Theoretically, construction should not be allowed in flood zones. Practically already

But even the best precautions can hardly prevent particularly endangered areas, such as along rivers and streams, from being flooded. "That's why no construction areas should actually be designated there", says Oliver Hauner, head of GDV's property and engineering insurance, loss prevention and statistics department. He emphasises the "actually" in his sentence, because in practice it happens again and again. The reason is the Water Management Act, Section 78 of which first prohibits construction areas in floodplains, but then defines no fewer than nine possible exceptions. "There's something for everyone", Hauner says. He sees this as a failure on the part of the legislature, which, unlike fire, for example, has still not recognised natural hazards as a protection goal in building and building code law. Switzerland and the Netherlands are further along. There, certain high-risk zones are strictly excluded from development. Wolfgang Dickhaut, professor of environmentally sound urban and infrastructure planning at HafenCity University in Hamburg, believes that the authorities lack foresight. “Most of those in charge are apparently convinced that it is cheaper to use aid funds every ten years to repair the damage caused by climate impacts than to adapt to them", he told Die Zeit. GDV expert Hauner would like to see a more holistic approach to the issue. He includes practical and regulatory preparedness by federal, state and local governments, individual preparedness by property owners and insurance coverage under a natural hazards policy.

"It must not be an economic decision not to insure against natural hazards damage despite the possibility of doing so and against one's better knowledge."

Almost every building is insurable against natural hazards. Must it still be a requirement?

It is precisely around the last point that a debate has flared up after the floods on the Ahr and Erft Rivers. In view of the disaster, there were calls for compulsory insurance against natural hazards. Jan-Oliver Thofern, managing director of the insurance broker Aon Germany, suspects behind this the widespread misjudgement that it is so far not possible to take out an insurance policy for many buildings due to the risk. “But that's wrong. There are insurance offers for almost 100 percent of all buildings. In my view, mandatory insurance is therefore not necessary", says Thofern.

"Society is suffering from flood dementia: After the catastrophe, the excitement is great, but a little later everything is forgotten."

Gert G. Wagner, a member of the German Council of Consumer Experts, is in favor of mandatory insurance. Premiums should depend on the individual risk and the provision made in each case. The economist believes that this will finally give the topic of prevention a firm place in the public debate. "Society is suffering from flood dementia. After a flood, the excitement is great, but a little later everything is forgotten again", says Wagner. This would be a thing of the past if there were risk-equivalent premiums. "For existing buildings, there could be government subsidies analogous to housing subsidies". Both agree that the insurance rate must increase. “It should not be an economically rational decision not to insure against natural hazards damage despite the possibility of doing so and against one's better judgment, because one trusts that in case of doubt, the taxpayer community will pay for the damage", Thofern says.

Text: Volker Kühn